Just like the accelerated adoption of remote working, the pricing of the Lower Mainland’s industrial land has been intensified by COVID-19.

In 2019, a research collaboration between Canadian Alliance Terminals and Rose Agency (formerly Collab Creative) illuminated an alarming trend that posed an imminent threat to 3PL providers and industrial supply chains in the lower mainland.¹ In the early years of the 2020s, the report advised, Vancouver could “literally run out of industrial land.” This claim was encapsulated by investigative journalism carried out by Natalie Wong for Bloomberg News, in which Wong discussed the challenges created by the potential land shortage with CBRE Ltd. Vice Chairman Paul Morassutti.² Now, especially following the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, we can reflect on this possibility and say with certainty that Wong, Morassutti, and our report were undoubtedly correct. Metro Vancouver is facing a critical shortage of industrial land and this choke point will have rippling implications for 3PL businesses across the region.

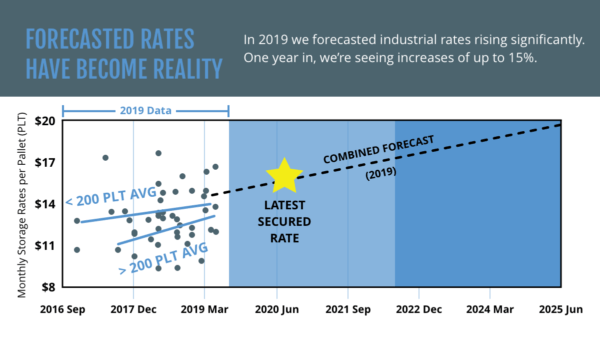

Because industrial storage (per square foot) costs have grown significantly, pallet storage rates (PLT) have grown accordingly.

To illustrate the impact these cost increases will have on 3PLs and related stakeholders, one needs only to reflect on the last four years. In 2017, industrial space could be leased for approximately $9.50 per square foot in areas of Metro Vancouver. In 2018, that number climbed to an average industrial asking net rental rate of $10.91 per square foot.¹ By mid 2020? “In our initial report, we forecasted a net rental asking rate of $15.00 per square foot, and our colleagues thought we were crazy,” says Canadian Alliance President William McKinnon. “We’re now seeing space lease agreements closing in the range of $14.00-$16.00 per square foot.” Indeed, the shortage of industrial land in Metro Vancouver has progressed to what seems like a breaking point. “And this trend,” says McKinnon, “it’s not going to slow down.”

Canadian Alliance President William McKinnon. “Our latest monthly pallet rates have now surpassed where we thought the market would go”

The historical year-over-year (2017-2018) increase of approximately $1.50 per square foot is a far cry from the nearly 175% jump between 2018 and 2020 revealing not only dwindling land supply but also the exertion of force from a series of external factors. The biggest factor this year, McKinnon believes, is the one you’d expect: COVID-19. “We were very concerned about supply chain disruptions earlier in the pandemic, when consumers were rushing to stock up on goods,” says McKinnon. “What we’re now seeing are the lasting implications of those initial disruptions and how companies have responded in anticipation of a second wave.”

E-Commerce Growth Disrupts and PPE Demand Where None Existed Before

The biggest changes impacting industrial land supply all involve sharp upticks in necessary inventory volume on hand. The first of the three largest trends results from a wide consumer shift toward e-commerce. “In addition to the rapid demand consumption experienced earlier in the pandemic, we’re seeing sustained growth in e-commerce that has not really declined since spring,” says McKinnon. In May, Canadian e-commerce sales hit $3.9 billion, representing a staggering 99.3% increase over February, before the pandemic saw Canadians enter lockdown protocols.³ This spike in demand has far larger shares of inventory parked in industrial warehouses across the lower mainland.

Further, a new spike in medical devices, chemicals, and personal protective equipment (PPE) has created a large stock in inventory which must be replenished and kept on hand that simply did not exist before in such large quantities. “While the influx of PPE is placing stress on warehouse supply,” says McKinnon, “it’s obviously a non-negotiable aspect of post-pandemic life. Further, as businesses stock up on PPE and demand remains high, this represents a meaningful source of job creation and preservation across Canada, which is something I’m very happy to see.”

Production & Operations Switching from Just In Time to Just In Case Supply Chain Management

Lastly, having witnessed the supply chain strain created by panic-buying earlier this spring and looking forward to an uncertain fall, many producers of consumer goods have switched from just-in-time forecasting to just-in-case forecasting. “Businesses want to avoid the stockouts we saw earlier this year,” says McKinnon, “and to do so, they’re systematically building up inventory to avoid those highly unpredictable international supply chain disruptions. Regretfully looking toward a potential second wave, businesses are trying to fortify inventory levels against the pandemic and this is putting a continued strain on warehouse supply.” This new supply chain behaviour closely reflects what Nassim Nicholas Taleb refers to as an “antifragile” model, wherein, “beyond resilience and robustness,” companies may, in fact, thrive on disorder.⁵

It’s impossible to know how the pandemic will continue to impact 3PL stakeholders and supply chain management internationally, but if this year is any indication, stakeholders should be wary of meteoric rises in warehousing space. “It’s not too late to take hold of a slice of the remaining space in Metro Vancouver,” says McKinnon, “but prices are going to continue to rise. The key will be longer term service contracts with warehousing suppliers and a clear forecast plan for growth to avoid potentially greater fallout from the pressures created by the global pandemic.”